How to ask for what you want

LeadershipCatherine Brenner, Louise Adler and Sam Mostyn offered their advic...

Become a part of the FW family for as little as $1 per week.

Explore MembershipsTurn words into action. Work with us to build a more diverse and inclusive workplace.

Learn MoreHear from notable women around the country on topics including leadership, business, finance, wellness and culture.

Mark your diariesTwo days of inspiring keynote speeches, panel discussions and interactive sessions.

Learn MoreCatherine Brenner, Louise Adler and Sam Mostyn offered their advic...

Em Rusciano outlines four lessons we can all take from her own sei...

In our latest series, Making The Case, Future Women's arguer-in-ch...

Putting survivors of family violence at the centre of the story.

Listen NowA program for mid-career women and exceptional graduates to fast track their career journey.

Learn MoreConnect with expert mentors and an advisory board of like-minded women to solve a professional challenge.

Learn MoreAs women spend a larger share of their lives as “old”, many are carving out new spaces for connection in both the physical and digital world.

By Emily J. Brooks

As women spend a larger share of their lives as “old”, many are carving out new spaces for connection in both the physical and digital world.

By Emily J. Brooks

There is a scene in season two of And Just Like That when Carrie Bradshaw arrives at her former Vogue editor’s apartment for a fundraiser. Gloria Steinem is in the room, surrounded by a sea of greying hair. The women in their sixties, seventies and eighties are there to raise money for the launch of an online magazine for older women. It is a moment where Bradshaw is forced to come to terms with the fact that she is a woman whose life and work is primarily of interest to the people in this room. It is a moment where Bradshaw reckons with the reality that she is, in fact, no longer young.

Womens’ relationship with age has been contentious for as long as time. In Susan Sontag’s famed essay, The Double Standard of Ageing, the author and critic observed that men don’t panic about ageing in the same way women do because they aren’t punished to the same degree. “Getting older is less profoundly wounding for a man, for in addition to the propaganda for youth that puts both men and women on the defensive as they age, there is a double standard about ageing that denounces women with special severity,” Sontag wrote. “Men are ‘allowed’ to age, without penalty, in several ways women are not.”

Men with greying hair and deepening lines on their faces are ‘silver foxes’, while women with wrinkles are not only undesirable but invisible to the male gaze. Older men are wise and authoritative, while older women are vulnerable and frail. This public perception extends into the workplace, with older women experiencing age discrimination earlier in their professional lives.

However, despite the double standard of ageing that still rings true today, women are outliving men in a society where humanity is living longer than ever before. Research shows there are twice as many Australian women than men aged 85 years and older, with the average man living to 80 while the average woman lives to 84. The Australian Bureau of Statistics also predicts that by 2050, there will be 1.8 million Australians aged 85 and older, compared to a mere 400,000 in 2010. So, as women spend a larger share of their lives categorised as “old”, many are reimagining this time, finding new ways of living and carving out new spaces for connection in both the physical and digital world.

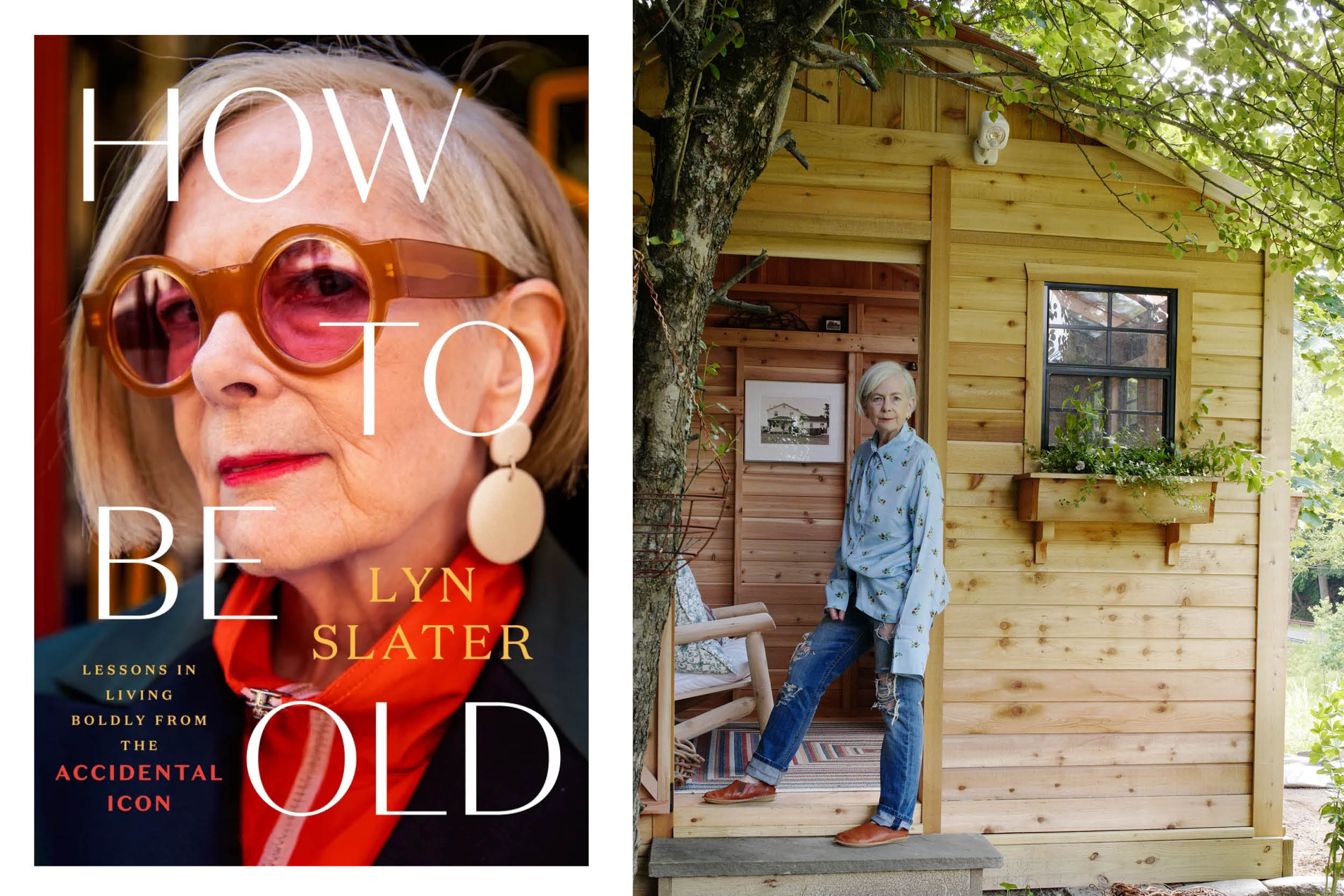

Joan Didion (L) for Céline in 2015 and Lyn Slater (R) for Valentino in 2016. Image credits: Juergen Teller, Courtesy of Céline, Terry Richardson Courtesy of Valentino.

Lyn Slater identifies as a person who does not remain satisfied staying in the same place for too long. “I have continuously reinvented myself throughout my life,” she tells FW from her home in Peekskill, a forty minute train ride from New York City, where she and her partner moved during the pandemic to be closer to family. Slater’s face is framed by a grey bob and pair of thick, black-rimmed glasses. She is petite and striking, wearing denim overalls as she speaks from her living room. Her personal style is something she has not only curated over the decades, but become well-known for.

Slater, 70, has had a long and varied career. She was a social worker, then a professor of social welfare and then an academic. But in 2014, after completing her PhD and publishing a textbook, she began to feel limited by academia and “was stimulated by the impulse to do something creative”. So, at 61, she started a fashion blog called The Accidental Icon. Slater’s partner, a photographer, would photograph her in outfits and she would write about everything from style to beauty to ageing. However, the blog wasn’t targeting women of a certain age, but a certain sensibility.

The site — and her Instagram account — began gaining traction. By 2016, there was something Slater describes as “a moment”. Not long after Joan Didion appeared in a Céline campaign donning big, black sunglasses and a grey bob, Slater appeared in another campaign for Valentino. “We were both intellectual women and neither of us camouflaged our white hair or our wrinkles in either of those campaigns,” Slater says. “There were a lot of young women who said, ‘Whoa, those two older women are so cool and they’re so hip and they’re so smart. Maybe we don’t have to be so afraid of being old.”

Not long after this ‘moment’, Slater was signed to a modelling agency, appeared at New York Fashion Week, and gained 400,000 new Instagram followers overnight. Her career as an influencer took off and the next few years were filled with international travel and sponsored posts and fashion weeks. But, after a while, she began to feel unfulfilled.

The pandemic is something she describes as ‘The Great Interrupter’. Like many of us, it was a time in her life where she was forced to reevaluate her priorities and her future. “I had come to two powerful understandings,” she says. “One was that, although a lot of people were telling me that I had moved the needle for older women being represented, I came to understand that I was still offering a very idealised representation of older life. The second was that I was desperately unhappy just posting sponsored posts on Instagram.” So she moved out of New York City to a smaller community to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren and started writing again.

Today, Slater’s Substack newsletter, How To Be Old, is a place where she pens essays to her nine thousand subscribers. She is one of many writers and creators in their fifties, sixties and seventies who have carved out online spaces to connect with thousands of other women. Emily Nunn, 62, writes the popular food and cooking newsletter, The Department of Salad, which reaches 52,000 readers each week. Kim France, 59, writes the style and pop-culture newsletter, Girls of a Certain Age, which is aimed at women over 40 and reaches 11,000 subscribers on a regular basis. While Valerie Monroe, 73, writes the popular beauty newsletter, How To Not F*ck Up Your Face, which is sent out to 15,000 subscribers.

Lyn Slater connects with women of all ages through her popular newsletter, How To Be Old. Her memoir of the same name will be released in March, 2024. Image credits: Supplied.

“Many women my age now are tech savvy. They are on social media, they use dating apps,” Slater says. “They use [technology] to find like-minded women to engage in conversations with, to make connections, to find their way to me.” She sees her readers as ‘co-creators’ of her community, which is made up of a majority-female audience and ranges from women in their twenties to their seventies. Women always read and consume content that helps them figure out who and how to be at the next age and stage, but for this demographic, it’s been missing for too long.

The creative feels most seen in the words of young writers on the Substack platform. She follows and admires writers including Anne Helen Petersen, Jessica Elefante and Sara Petersen. “I identify much more with these younger writers who are writing about culture and burnout and social media. My generation is not writing about that,” Slater says. She notes that while older women are now on Instagram and many have a desire to be influencers, there aren’t many who have already been through it. “I didn’t have anyone in my age group that could understand what had happened to me. So I have been connecting with younger women writers who are writing about social media and youth and beauty standards and the internet and all of these things that happened to me because I was on the internet,” she says.

“Many women my age now are tech savvy. They use [technology] to find like-minded women to engage in conversations with, to make connections, to find their way to me.”

When she moved out of New York City to Peekskill, Slater also began writing her memoir, How To Be Old, which will be in bookstores from March next year. The memoir documents Slater’s sixties – that ten year period where her creative career exploded onto the public stage – and showcases the ways in which women can reinvent themselves, time and time again. “Ageing is like any other time of your life,” she says. “There are parts that are incredibly wonderful and there are parts that really suck. But there are many, many creative opportunities for you to respond to those challenges. I hate to say it, but that’s how I felt when I was twenty. That’s how I felt when I was thirty. It happened to me in my forties and my fifties. So it’s the same, but different.”

Her next goal is to create a space for women to have more intergenerational conversations, so that we can come up with creative solutions to tackle universal problems for our gender — from childcare to beauty standards to the double standards of ageing. “We are siloed and the media loves to pit us against each other but we have many common issues that impact us greatly,” she says. “If we were all working together, we would be much more likely to make a change.”

She has noticed and is impressed by the ways in which young women are discussing and actively resisting the beauty standards that continue to exist today. “Because they’re having the courage to begin to deconstruct this, older women and myself have a responsibility to show them, you know what, you don’t have to spend eight hours a day being thin and putting makeup on,” she says. “You can do really meaningful, amazing life-giving things with that time and money and energy and a lot of women my age are doing that.”

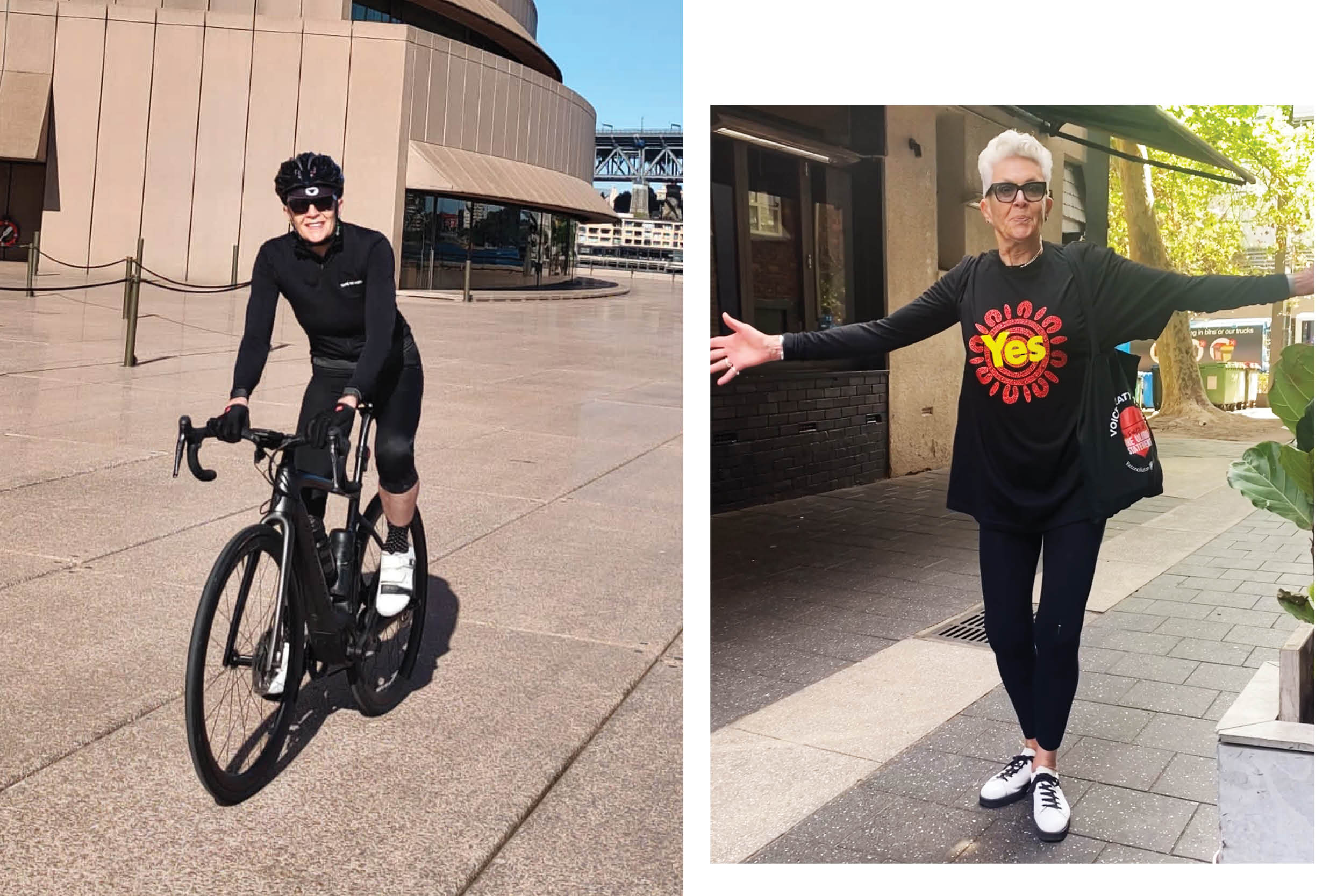

Elizabeth Darlison, 78, finds meaning and connection through her work, volunteering, family and cycling.

FW first noticed Elizabeth Darlison when she was standing on the corner of Macleay Street in Potts Point, Sydney, handing out flyers in a t-shirt with the word ‘Yes’ emblazoned on the front. Darlison, 78, had been volunteering for Australia’s Voice to Parliament’s ‘Yes’ campaign in the final weeks before the vote but she has a long-held interest in social change.

The single mother-of-two grew up in Alice Springs, forming close friendships and a strong connection to the Arrernte and Warlpiri people. This shaped her view of the world although she didn’t know it at the time. After being sent to an all-girls public school in Sydney, Darlison became a teacher, then an academic, then a government bureaucrat in Canberra. She eventually founded her own social policy, management and research consultancy, The Miller Group, where she still works today. Although she is slowly stepping back from her working life to prioritise something else — volunteering.

She isn’t alone here. Research from the Australia Institute reveals rates of volunteering among the ‘baby boomer’ generation are continuing to rise compared to previous generations. This group is retired, healthy and wanting to contribute to their communities. A renewed focus on our local communities is something Slater has also observed in the United States. “One change that older women made during the pandemic – and after – was to become much more focused on their local community, making connections doing volunteer work or becoming an activist on a small local level,” she says. “These are places and spaces where they feel that they can be seen, where they are visible within those communities.”

Darlison teaches ethics at a primary school two mornings a week and hopes to volunteer to more social change campaigns. She’s always had a strong sense of what a “healthy, connected, sustainable community” is and believes that everyone should have as many opportunities as possible to maximise their potential. Volunteering is one way of fighting for a community where this exists.

“I’ve had a very fortunate life,” she says. “I’m not wealthy but I am white. I’m middle class. I have had a great education. I have a lot of privileges as a consequence of that and I never take that for granted. So if I can spend some of my time working with people who’ve not had those opportunities, then that’s a great thing to do.”

As she approaches 79, Darlison tells me she is also making more room for life. The business owner, who lives in Elizabeth Bay, has three grandchildren and two sons. One of her sons recently passed away, but she counts both of their partners as family. “I realised that I want to spend more time with my friends and family and also just enjoy life,” she says. “You know, going to see more movies, reading more books, doing more surfing.”

Darlison has surfed since she was a teenager but, today, she tends to stick to bodysurfing. Over the summer, she plans to ride her bike down to the beaches of Tamarama and Bronte to spend more time in the ocean. Riding has always been her “main form of transport”. She was given her first bike at the tender age of four and rode her own children to school most mornings. When she was in her early sixties, one of her sons encouraged her to join a cycling group.

“He said, ‘give it a go’ and so I did. In addition to using my bike daily to commute, I have been road riding with different bunches ever since,” she says. “I’ve always thought that there’s a great sense of empowerment for women through control of your body and a sense of being able to trust your body. That’s always been really important to me and I love being active. On the days when I don’t cycle or I don’t go to the gym, I really notice it.”

Today, Darlison rides thirty to forty kilometres each morning with the women in her cycling group. Most could be mistaken for her daughter, she tells me, if not her granddaughter. But, each morning, after their ride, they will have coffee together at one of the local cafes. Over time and many coffees, she has formed close and important friendships. “A lot of those women are a lot younger than I am,” she says. “But what I have found over the years is that my intergenerational friendships have been really important.”

Intergenerational friendships have been integral to the quality of both Slater and Darlison’s lives. And these days, at her local coffee shop, Slater has noticed the variety of people who fill it each morning, from toddlers to women in their eighties and nineties. “It’s sort of like a microcosm of our community. You see people of every age in conversation with one another,” she says. “Women have told me that they move from places where they don’t feel visible or valued and they find other places to live.”

If you’re not a member, sign up to our newsletter to get the best of Future Women in your inbox.